October 30, 2015

Visit to the Royal Astronomical Society Library – October 2015

Report by: Andy Sawers

Imagine being at a gathering where the guest list includes Galileo, Copernicus, Isaac Newton, Edmond Halley, Caroline Herschel and John Flamsteed.

That’s pretty much what it felt like as 16 members of the Flamsteed attended our third visit to the remarkable Royal Astronomical Society library at Burlington House in Piccadilly.

RAS librarian Dr Sian Prosser was our host for the visit, and she set out on display some of the most fantastic and historically important books.

Questions were very welcome, of course: “And if I can’t answer any question,” Sian quipped, “well, we’re in a library, so we can always look it up!”

One of the most prized possessions on display was a copy of Isaac Newton’s Principia, which set out his universal law of gravitation. Only around 300-400 copies of the first edition were printed. Auction house Christie’s sold a private collector’s copy in July for £278,500!

The copy on display also unfolded the drawing of the orbit of a comet, showing that it is an extremely eccentric orbit.

By the way, Principia is the European Space Agency mission name for UK astronaut Tim Peake’s long-duration flight on the International Space Station, beginning in December.

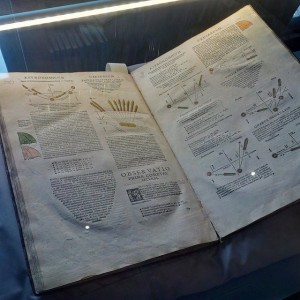

Talking of comets, a remarkable book was on display, Astronomicim Caesariu (1540), by Peter Apian, opened at a page which shows the 1531 appearance of Halley’s comet long before it was ever known by that name.

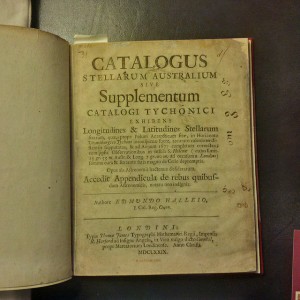

We were also privileged to see Cometographia (1663) by Johannes Hevelius and Edmond Halley’s catalogue of the southern stars, which he compiled on St Helena, having decided that going south would be a better way for him to make his mark rather than competing with all the European astronomers in the north. Halley’s catalogue earned him the sobriquet ‘Our southern Tycho’, bestowed upon him by none less than John Flamsteed.

Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius was on display, opened at the pages showing how the Moon’s terminator appeared irregular or smooth, depending on whether the Moon’s surface at any particular point had mountains, craters or smooth ‘seas’. Until Galileo pointed his telescope lunarwards, prevailing wisdom had it that the Moon, like all other celestial objects, were ‘perfect’ spheres. His book was first published in 1610, shortly after he developed (but didn’t invent) the telescope.

We were reminded of other implications of the ‘imperfections’ on the Moon by the portrait gazing down at us of Francis Baily, four-times president of the Royal Astronomical Society and the man who gave his name to ‘Baily’s beads’, which appear just as the Moon is covering or uncovering the Sun in a total solar eclipse.

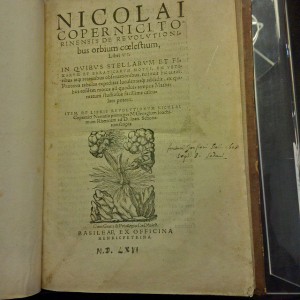

Another wonderful treat was Copernicus’s De Revolutionibus – the book that placed the Sun at the centre of the Universe, rather than the Earth. Intriguingly, the book on display was the second edition of 1566 – 23 years after Copernicus’s death. (History has it that Copernicus received a copy of the first edition straight from the printer while he was on his deathbed – and then promptly keeled over.) The second edition was published by Hentricus Petrus, or Henric Petrina as set out on the title page.

2015 being the Unesco International Year of Light, Sian also set out a book called Opticae Thesaurus. This is a 1572 publication but based on a 13th century Latin translation of work on optics conducted by Ibn al-Haytham, who lived 1,000 years ago. He believed in the experimental approach to science – entirely at odds with the then-prevailing Aristotelian philosophy and hundreds of years ahead of his time.

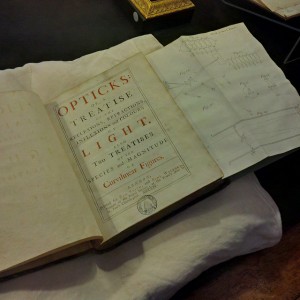

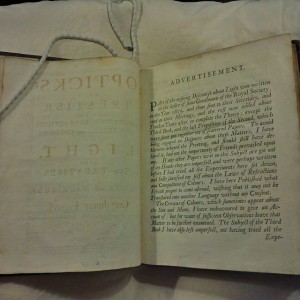

Also on display was Isaac Newton’s Opticks, published in 1704. It was interesting to note that, while Principia was published in Latin, Opticks was published in English – though the way Newton wrote, I’m not sure if that made it any more readable.

Finally, one exhibit was particularly special for Flamsteed members – and gave a ‘two for the price of one’ bargain. Sian set out a very special copy of John Flamsteed’s posthumously-published 3,000-star Atlas Coelestis (1729): it was Caroline Herschel’s personal copy, and annotated by her. As one of our members said: Normally you would get annoyed if someone scribbles notes in a book like this. In this case it makes it even more interesting. (Our photograph shows Dr Sian Prosser and Brian Blake with the Atlas.)

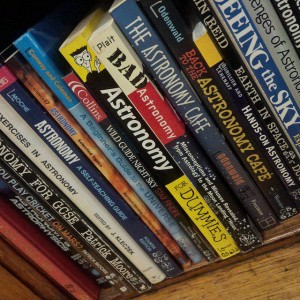

The RAS library is the sort of place where you actually feel clever just by being there – as if all that wealth of astronomical knowledge can be absorbed by osmosis without actually having to read anything. But if you feel at all intimidated by it, take comfort from the fact that even the RAS has on its shelves titles such as this:

Our thanks once again to Sian and the RAS for another very memorable visit.

Pictures from the Trip (by Andy Sawers and Nick Christodoulou):

Posted under: Flamsteed, History of Astronomy, Meeting Report, Society Trip

You must be logged in to post a comment.