September 16, 2013

Photographing the Universe

Dr Marek Kukula

Report by: Mike Meynell

The Flamsteed were delighted to welcome back our good friend, Dr Marek Kukula, the Public Astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, who came to give a ‘behind the scenes’ view about the process that led to the recent ‘Visions of the Universe’ exhibition. The exhibition was an unqualified success, with over 70,000 visitors and some fantastic reviews by the critics.

Marek stated that the exhibition and the broader public programme at the Royal Observatory are designed to communicate the idea that astronomy is deeply embedded in human culture and history.

Turning information from wavelengths right across the electromagnetic spectrum into images that we can see is central to virtually all astronomy. For over 300 years, people have been imaging the sky, either by hand drawing or by photography.

The idea behind the exhibition was to look at the process of imaging and looking at the results of that imaging process, communicating the science that is embedded within the images.

Until the invention of photography, we were limited by what the human eye can see and the skills of the astronomer in drawing the image. It took several decades after the invention of photography for the technology to have advanced sufficiently to allow images to be taken of objects in the night sky. There were several problems to overcome, not least compensating for the continual rotation of the Earth so that long exposures could be taken. Once this was perfected, the camera could be used to record more light coming from the object than can be picked up by the human eye. This meant that far more detail could be recorded as the photographic plates became more sensitive.

The limits of photography using photographic plates was reached by the 1970s, when David Malin perfected techniques to extract the maximum amount of detail from faint low contrast objects. Further advances were not possible as there were limitations in the grain size of particles in the photographic emulsion. It was at this point that astronomers started looking for alternatives – and they started to concentrate on charge-coupled devices or CCDs.

Obviously, nowadays, we take these devices for granted as they appear in cameras on our mobile phones. This technology was developed by astronomers in the 70s and 80s and would not have existed were it not for the advances made by astronomy over the last few decades.

Advances in telescopes have also made a huge difference in what we can see in the night sky. Galileo’s telescope could only just resolve that Jupiter was a disc, but this was enough to discover that Jupiter had its own moons. Galileo was also able to observe that Venus had phases, meaning that it had to be closer to the Sun than the Earth. These observations completely changed our model of the Universe and the perception of our place within it.

The use of Camera Obscura technology to project images on to a screen for many people to view became particularly prevalent in the 17th and 18th centuries. John Flamsteed used the camera obscura at the Royal Observatory to make observations of the Sun.

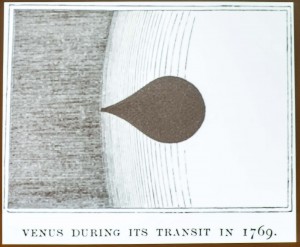

In 1716, Edmund Halley published a paper that demonstrated how accurate measurements could be made to derive the distance from Earth to Venus, and thereby the distance from the Earth to the Sun, by observing the duration of a transit of Venus across the disc of the Sun from different latitudes. Halley knew that he wouldn’t live to observe the next transit of Venus in 1761, but his technique was used. Unfortunately, a phenomenon known as the ‘black-drop effect’ meant that it was very difficult for observers to measure the exact time that Venus’s disc touched the inside edge of the Sun. Until it was possible to record the image on a photographic plate with larger telescopes and better optics, this continued to be a problem.

In the 19th century, Sir John Herschel became famous not just because of his work in astronomy, but also because of his important contributions to advancements in photography. Herschel was to the first to coin the word ‘photography’ and also apply the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ to photography. He also invented one of the chemical fixing processes for photography. Astronomy therefore has a hand in the invention of photography itself.

In the late 19th century, photographic techniques had advanced to such an extent that it was the main technique used for measurements in astronomy. The 1874 and 1882 transits of Venus were recorded photographically and the measurements enabled a much more accurate Earth-Sun distance to be determined.

In 1919, Arthur Eddington took pictures of a solar eclipse and determined that Einstein’s theory of general relativity was valid as stars with light rays that passed near the Sun appeared to be slightly shifted because their light had been curved by the Sun’s gravitational field. So a photograph proved the theory of general relativity.

In 1924, a photograph taken by Edwin Hubble fundamentally changed our view of the universe. He took a photograph of the Andromeda Galaxy, which was then known as the Andromeda Nebula as the prevailing view was that the universe consisted only of the Milky Way galaxy. This photograph showed a Cepheid variable, which proved that the nebula was too distant to be part of our Galaxy so were, in fact, galaxies on there own. Photography showed that the universe was billions of times bigger than we thought before.

More recently, using the Hubble Space Telescope, a ‘deep field’ image showed that that there must be over a hundred billion galaxies in the known universe.

Advancements in camera technology have meant that images can be taken by amateurs using relatively basic equipment that are far better than some of the most advanced images taken only a few decades ago. This is what inspired Marek and his team to bring about the “Visions of the Universe” exhibition, a job that he did fantastically well.

Our sincere thanks to Marek for giving such a fascinating and engaging talk to the Flamsteed once again.

Posted under: Flamsteed, Flamsteed Lecture, Meeting Report

You must be logged in to post a comment.