April 22, 2013

King’s astronomer, professor or public servant? John Flamsteed and the role of the Astronomer Royal

Dr Rebekah Higgitt

Report by: Mike Meynell

Coinciding with the launch of the Flamsteed “History of Astronomy” group, we were delighted to welcome Dr Rebekah Higgitt who is Curator of History of Science and Technology at the Royal Observatory Greenwich & National Maritime Museum.

Rebekah came to discuss the role of the Astronomer Royal in the early days of the Greenwich Observatory, focussing on John Flamsteed. Prior to this lecture, we had our usual ‘Sky this Month’ feature, with an excellent talk delivered by Chris Mann. This presentation can be found on the Flamsteed website.

Rebekah’s lecture was a fascinating insight into the role of the Astronomer Royal in Flamsteed’s time. It helped to explain why there were so many clashes between Flamsteed and his peers at the time, as different people had different interpretations of what the role of the Astronomer Royal should encompass.

Flamsteed’s well-known conflict with Isaac Newton is perhaps the best-known clash, as Flamsteed’s refusal to publish his observations infuriated Newton, who wanted the measurements to prove his own lunar theory. This eventually led to a rushed and error-strewn version of ‘Historia Coelestis Britannica’ being published without Flamsteed’s permission in 1712, which caused Flamsteed to buy up every copy he could, before burning them at the Royal Observatory.

The problems with defining Flamsteed’s role are perhaps summed up by the fact that the term ‘Astronomer Royal’ was not used at the time of his appointment. Rachel referred us to a number of job titles for Flamsteed that had been used:

- In the Royal Warrant at the formation of the observatory, the position was described as “Astronomical Observator”;

- Flamsteed himself preferred the title “Mathematicus Regius”;

- In Flamsteed’s catalog, published posthumously, he is referred to as “Regius Professor of Astronomy at Greenwich”;

- John Evelyn referred to Flamsteed as “The King’s astronomical professor”;

- Finally, Henry Oldenburg at the Royal Society referred to Flamsteed as “The head of the astronomical observatory lately constructed at the King’s expense”!

Clearly, there are different degrees of status, responsibility and expectations implied by each of these job titles.

The siting of the observatory in Greenwich, within a Royal Park and so close to the Thames, highlights the royal connections inherent with Flamsteed’s role. There was a ceremonial aspect to the job, made all the more prevalent by the fact that the observatory building itself was designed by Wren with an element of ‘pomp’ and can certainly not fail to impress any passer-by who sees its dramatic vista atop the hill in Greenwich Park.

However, Charles II never came to the observatory, not even to its opening. Flamsteed would probably have preferred the observatory to be placed nearer to court. In the end, however, this lack of royal patronage probably played in Flamsteed’s favour as it meant that there were closer relationships with Government, so Flamsteed’s position was secure after Charles’s death. By the time of Flamsteed’s death, he had served 5 different monarchs, with the position of Astronomer Royal continuing in perpetuity and not linked to an individual monarch.

Even from his early days at the observatory, Flamsteed undoubtedly had many frustrations in his role and complained of “being troubled with the impertinences of a crowd of visitants” and of being forced to publish papers and writings before he thought they were ready. Rebekah postulated that this led to Flamsteed thinking about his task as his “life’s work” which would all be published at once, a lasting monument to him and his position, whilst laying the basis for positional astronomy.

Increasingly, Flamsteed thought of himself as the heir to Tycho Brahe. Flamsteed owned two portraits of Brahe. He also had great interest in improving the quality of instrumentation and measurements, leading many to refer to him as the successor to Jeremiah Horrocks.

Flamsteed had more freedom to focus on the things that he wanted to, since he secured the patronage of Jonas Moore, who is remembered as the man who proposed the establishment of the Royal Observatory in 1674. Moore supplied Flamsteed with instrumentation, often as gifts directly to Flamsteed rather than the Royal Observatory. This explains why, after Flamsteed’s death, his wife took the instruments out of the observatory and sold them. It also explains why Flamsteed felt that he owed allegiance to Moore personally, rather than the wider public.

Flamsteed did not feel that he should share data automatically without getting something in return and in this approach he behaved very much like a private individual rather than someone who was providing a service to all.

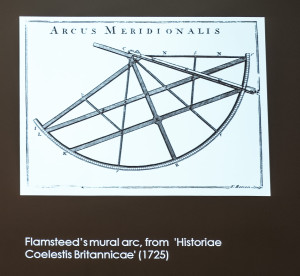

It was the arrival of a new piece of equipment, the Mural Arc in 1689, which allowed for even more accuracy in the measurement of the positions of stars. Flamsteed paid for this instrument himself from inherited money.

The observatory, of course, was built to improve navigation at sea and “find the so-much desired longitude of places” by astronomical means. This was to be done by improving the measurements of the planets and stars. Flamsteed was not a big fan of using the ‘lunar-distance’ method for solving this problem, for which accurate star charts were vital, instead concentrating on using the motions of Jupiter’s satellites. However, through the use of the Mural Arc, the measurement of the stars became sufficiently accurate to use the lunar-distance method after Flamsteed’s data was published in 1725 (after his death).

Flamsteed never had an easy relationship with the Royal Society, though many of his papers were published through the society. When Newton and Halley became the pre-eminent astronomers within the Royal Society, Flamsteed position within the society diminished. Newton and Halley both highlighted the “public service” role of the Astronomer Royal, talking about how science could serve the monarch and the nation. Also, practical astronomy came to be seen as subservient to the mathematical theories that were being formed at the time. Astronomers were seen as people who would serve the mathematical theories with practical observations. Newton and Halley ensured that this culminated in Flamsteed being effectively supervised by a new “Board of Visitors” to the Royal Observatory, which was established by Royal warrant in 1710. This very much flew in the face of how Flamsteed believed he should operate… rather than directing his own work, he could now be ordered to do the work that the Royal Society believed he should do. This was, in Flamsteed’s view, the ultimate insult.

So, in conclusion, Rachel said that there was some truth in all of the types of role that Flamsteed inhabited: King’s astronomer, professor or public servant; royal, private and public. This was, though, a new kind of role, which was clarified in the decades after Flamsteed’s death. Uncertainties remained for a very long time, particularly in relation to purchasing instruments and publishing results.

Others clarified the role further. Nevil Maskelyne was the first to decide that the Astronomer Royal had to publish regularly. It is with him that we see the publication of Greenwich observations annually and the Nautical Almanac, items that are clearly of use to a wider public.

George Airy defined himself as an advisor to Government on a whole range of issues, compartmentalising his Astronomer Royal duties alongside many others. These changes reflected the changing role of science within society and the wider professionalisation of science away from the gentleman scientist.

Flamsteed was in a unique position in his time. There was no one else in a Government-funded position at that time, so he couldn’t model himself on anybody. By Airy’s time, there were many in a position of public service. The role of Astronomer Royal took centuries to figure out. Flamsteed had the problems that he had because no one could agree on what it was he should be doing.

The lecture concluded with a question and answer session.

Our huge thanks go the Rebekah for her fascinating lecture and we wish her all the best of luck in her new career when she leaves the museum in September.

Pictures from the Evening (by Mike Meynell):

Posted under: Flamsteed, Flamsteed Lecture, Meeting Report

You must be logged in to post a comment.