March 11, 2013

Exploration of Subglacial Lake Ellsworth, West Antarctica

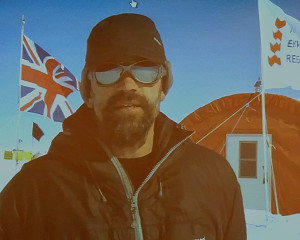

Professor Martin Siegert

Report by: Chris Sutcliffe

The Flamsteed were delighted to welcome Martin Siegert, who is Professor of Geosciences at the University of Bristol.

Martin is a glaciologist, which may have left many attendees wondering why he was giving a lecture to an astronomy society! All became clear when Martin explained how he was the principal investigator of the Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC) Lake Ellsworth Consortium, a project which is tasked with searching for life in the extreme environments found in subglacial lakes. Europa may have a water ocean beneath the icy crust of its surface, as it is heated by tidal flexing as it orbits around Jupiter. If life is found in subglacial lakes, it opens up the possibilities for finding life on Europa and other such worlds. The lessons learned in exploring for life in these environments is helping the planning of any future mission to Europa. The Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) mission is planned to arrive at Jupiter in 2030 and will use ice-penetrating radar to research the subsurface detail of the Jovian moons.

Sadly, the mission to explore Lake Ellsworth had to be called off at the end of last year, due to equipment problems. Martin’s talk was about what the project hoped to achieve, what went wrong and plans for the future of the project.

There are 379 known subglacial lakes in Antarctica. Lake Ellsworth is approximately 10 km in length and 2 or 3 km wide, with a water depth of about 150 metres. It is located under approximately 3.4 km of ice. The plan was to drill down to the lake using a hot water drill.

At the outset, a geophysical survey was undertaken and a drill system and probe was designed and manufactured. A comprehensive environmental evaluation document had to be written, which is a pre-requisite for performing any work in Antarctica. It was critical that there would be no contamination of the lake, not just from an environmental perspective, but also to ensure that any microbes that may be detected in the lake actually resided in the lake and had not been brought down by the drilling equipment.

Union Glacier in the Ellsworth Mountains (approximately 600 miles from the South Pole) was the base camp, which has its own runway enabling access by Ilyushyn II-76 aircraft flying supplies from Chile.

A boiler capable of heating water to 90 degrees C for pushing at 2,000 pounds per square inch was used to create a cavity using different bore holes. The hot water drill is designed to cope with extraordinary environmental conditions. The drill needs to operate continuously for 3 days to create a 360 mm wide borehole through the ice into the lake.

Prior to drilling, it was necessary to rebuild an exploration probe that was cleaned to an ultra sterile state to avoid contaminating the lake. Hydrogen peroxide was used for this purpose.

Martin took us through a diary of events for the expedition in December 2012: –

1 DECEMBER: 12 people were at the camp with 120 barrels of fuel for the boiler. The boiler heats the snow, which is shovelled into huge onion-shaped tanks. 90,000 litres of hot water is required just to get through the top few metres of the ice sheet.

2 DECEMBER: A shovel was used for the first metre of ice!

3 DECEMBER: The drill system starts working.

4-5 DECEMBER: The deployment system was tested and the sterile probe was put into the borehole, taking care to prevent contamination from the atmosphere. Also on 5 December, the boiler control panel failed, so the spare board was fitted. A replacement board had to be ordered from the UK, but would take 10 days to arrive.

6 DECEMBER: Various boiler valves cracked and there were a few faulty gauges.

7 DECEMBER: The drilling system was in order.

10-11 DECEMBER: The boiler was switched on with the refitted control panel, and to everyone’s relief, it was working well.

12 DECEMBER: Snow shovelling into the onion tanks.

13 DECEMBER: The boiler was smoking too much, probably due to the altitude (2,000 metres above sea level), as this problem had not been experienced in Cambridge. However, the umbilical hose to make the cavity drilled for 60 metres, but it was losing too much water. It was noted that the drill nozzle was bent, meaning that they may not have been drilling vertically.

14 DECEMBER: More snow shovelling.

15 DECEMBER: Very bad news. The second boiler control board failed, and it was agreed to wait for the third control board to arrive.

17 DECEMBER: It was found that the control boards had faulty variable resistors (varistors).

20 DECEMBER: The spare control board arrived from the UK.

21 DECEMBER: Efforts to restart the boilers proved difficult, as the control board had to be reprogrammed.

22 DECEMBER: Drilling recommences, and the boiler was working well, but there was a bent nozzle in the umbilical again. Drilling was down to 300 metres and the creation of the cavity was started.

23 DECEMBER: Drilling of the main hole commenced. The first task was to drill 300 metres and connect to the main cavity before drilling down to the lake. The generator started at 16:20 but stopped suddenly at 19:45; one of the generators had short-circuited and caused a shutdown of the whole system. The drilling continued with the two remaining generators, but they had to operate at a higher capacity.

24 DECEMBER: By 6am, they believed that they had reached the cavity. However, by the afternoon, it was obvious that major water loss had occurred and they hadn’t reached the cavity. Drilling continued, but the umbilical became stuck; either jammed up, or frozen in. The link between the two boreholes at 300 metres depth could not be made, despite trying for over 20 hours.

25 DECEMBER: Drilling ceased because there was no longer sufficient fuel to reach the lake; also the team was exhausted with shovelling, and ultimately they had to cut the umbilical. It was a very tough day! The expedition was called off.

The logistics of the expedition had worked superbly and the boiler worked well eventually, but, often, it did not get up to temperature when needed. However, major problems were: –

- The drill nozzle became bent when put into the ice sheet, meaning that they were not drilling vertically. This made it very difficult to line up the two drill holes to reach the cavity.

- There was not enough fuel.

Martin explained that the expedition failed because of the failure to link to the cavity; the fuel problem; and problems with the boiler. These problems were relatively modest and Martin believes them to be solvable.

It is now proposed to continue the expedition in 2015 or later, giving time for the drilling system to be serviced and modified.

Antarctic research (just like space science) is very difficult and the boundaries of technology and human endurance, in the harshest weather conditions on Earth, are pushed to the limit. This is all valuable experience, as our approach of these expeditions will help to determine the best approach to the exploration of the sub-surface oceans of Europa.

This was a most interesting lecture and one felt truly involved in the expedition. Martin concluded by answering questions. We wish him and the Lake Ellsworth team all the very best for any future expedition.

Pictures from the Evening (by Malcolm Porter):

Posted under: Flamsteed, Flamsteed Lecture, Meeting Report

You must be logged in to post a comment.