December 3, 2012

Solar Secrets: Understanding our Star, the Sun

Brendan Owens

Report by: Mike Meynell

The Flamsteed had the great pleasure of welcoming Brendan Owens from the Royal Observatory Greenwich for our 2012 Christmas lecture. Flamsteed members enjoyed mince pies and chocolate biscuits with their tea and coffee on arrival, to get into a festive mood. We were also very grateful to the museum for arranging to open the museum shop for members to do a little Christmas shopping prior to the lecture. When I looked in, they seemed to be doing a roaring trade.

Grey started the evening’s entertainment with a quite extraordinary Santa Claus impression. Thank goodness he wasn’t dressed in full Santa regalia, else his rendition of ‘Merry Christmas’ would have had the real Santa quaking in his reindeer skin boots! A new career beckons, methinks.

Grey had arranged to bring some of our new Solar observing equipment from the observatory, along with the radio astronomy equipment – namely the satellite dish and the Very Low Frequency (VLF) receiver. We displayed the latest set of data that Clive Inglis had gathered with the VLF receiver. This included the detection of two solar flares. Details of the latest news from the Radio Astronomy Group can be found in this website report, whilst the Solar Flares video can be seen here.

A real highlight of the evening was the presentation of honorary membership of the society to Jane Bendall. Jane was one of the driving forces behind the foundation of the society back in 1999 and has, ever since, served on the Flamsteed Committee as Programme Secretary, Membership Secretary and, until Asra took over earlier this year, Committee Secretary. She is now in the process of handing over her role as Programme Secretary to Brian Evans, but will continue in her membership role for the time being. Now she is taking more of a back seat, we felt that this was an appropriate time to recognise all of the wonderful work that she has performed in growing the society from an initial 15 people to over 300 members today. Malcolm gave a speech outlining the history of the society and Jane’s role, which was very well received. We were delighted to welcome Dr Francisco Diego back to the Flamsteed, who came especially to present an honorary membership certificate to Jane. Francisco had given the very first Flamsteed lecture in October 1999. A history of the first 10 years of the society, made for the 10th anniversary celebrations in 2009, can be found on the old website here.

Prior to the main event of the evening, Grey gave an update on Stargazing Live followed by my brief presentation on what to see in the night Sky this Month.

Then it was time for Brendan to take the stage and he treated us to a fascinating and informative lecture about the Sun, delivered in his inimitable upbeat style.

Brendan started with an explanation of Sunspots, explaining that the first documented reference to Sunspots dates back to around 800BC. Though it is very dangerous to view the Sun with the naked eye, it has been possible to view solar features through the thick smoke generated by forest fires. The first sketches of sunspots were made in the 12th century, by the monk John of Worcester. Extraordinarily, these drawings depict both the umbra and the penumbra of sunspots. Quite an achievement. Some early observers thought that sunspots were planets transiting across the face of the Sun, but we now know that they must have been observing sunspots.

Brendan explained that sunspots are around 2000°c cooler than the surrounding area, which is why they appear darker. However the temperature of sunspots is still around 4000°c. So, how did the sunspots get there? The explanation of this required the development of observations using consequences of the ‘Zeeman effect‘. Light is effected by magnetic fields and it was therefore found that sunspots are a magnetic phenomenon.

We were then treated to a description of the Dallmeyer Photoheliograph, which currently resides in the Altazimuth Pavilion at the Royal Observatory Greenwich. First commissioned in 1871, the observatory hopes to bring the instrument back into use next year for public displays. The instrument was used to photograph the Sun and has a simple projector box on the rear of the telescope where observations of sunspots could be made. Solar observations moved from Greenwich to Herstmonceux in 1949, but, on the last day of Greenwich observations, the first day of observations at Herstmonceux began, leaving an uninterrupted record of solar observations up until 1971.

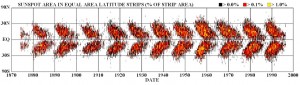

Brendan then gave an explanation of the ‘butterfly diagram‘ which shows the latitude of sunspot occurrence plotted against time. First described by E.W. Maunder of the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1904, it shows how sunspots move from high latitudes at the start of the 11-year solar cycle to latitudes close to the Sun’s equator at the end of the cycle (at the peak of solar activity).

Joseph von Fraunhofer showed that there were ‘gaps’ in the solar spectrum, which were later shown to be atomic absorption lines from different elements within the Sun. In fact, many elements on Earth were only discovered via analysis of the solar spectrum. For example, Helium was first discovered in 1868 as a result of observing a yellow line in the solar spectrum which did not match any other element. It was named after the Greek word for the Sun, helios, as a result.

We can also listen to the Sun. The Sun vibrates from a complex pattern of waves. Researchers at Stanford University took this data and sped it up 42,000 times, compressing 40 days of vibrations with a few seconds, the results of which can be heard here. The study of wave oscillations in the Sun is known as helioseismology, and from this science it is possible to learn about the Sun’s interior.

Brendan moved on to talk about some of the satellites which are dedicated to solar research. Brendan worked on data provided by SOHO, which, though launched back in 1995, is still the main source of solar data for space weather prediction. However, as regards quality of images, SOHO has now been superseded by SDO, launched in 2010. The images recorded by this satellite are simply amazing and cover a wide range of different wavelength bands from visible light to extreme ultraviolet. It is possible to view these images for any part of the Sun at any time, using the Helioviewer application on the web.

So, what happens when a solar storm hits the Earth? Fortunately, Brendan explained, the magnetosphere of the Earth protects us, although charged particles are able to penetrate at the poles, leading to the formation of aurora. Bigger solar storms have led to aurora being visible as far south as Rome. Solar storms can cause problems with satellites and power networks and they have even generated ground current, particularly in the solar storm of 1859, when telegraph operators found that they could still send and receive messages even with their equipment disconnected from the power supply!

We could expect more storms over the next year or so, as the Sun builds up to solar maximum. However, as it takes 2-5 days for the charged particles to reach us, our continual surveillance of the Sun (particularly from the STEREO satellites) should make it possible to prepare for a storm, by turning satellites away from the storm and by regulating power supplies. It is possible for members of the public to get involved in detecting solar storms via the excellent Solar Stormwatch website.

Brendan pointed out a very useful website, solarstorms.org, which has a fascinating archive of newspaper cuttings dating back to 1859 on solar storm activity.

To conclude the lecture in a festive spirit, Brendan finished with his own interpretation of the Christmas Tree Nebula, with Solar baubles added to good effect.

Our thanks to Brendan for coming to the Flamsteed and for delivering such an engrossing lecture.

Pictures from the Evening (by Grey Lipley and Malcolm Porter):

Posted under: Flamsteed, Flamsteed Lecture, Meeting Report

You must be logged in to post a comment.