June 6, 2012

‘Transit of Venus’ on Blackheath

Report by: Grey Lipley

Around 140 people gathered on Blackheath at 4.30am on the morning of 6 June 2012 to observe The Transit of Venus. With a thick bank of billowing slate grey cloud to the east, it was not a promising start. Never one to be put off, I unpacked the car which was loaded with Coronado telescopes of varying size together with motorised mounts, tripods, a table and literature.

Flamsteed members enthusiastically transported and assembled the telescopes which mingled with other equipment belonging to visitors from far and wide. As a large group with single purpose, we stood expectantly beneath a cloud streaked sky. There was a great sense of occasion and much excitement as the minutes passed. With light levels increasing rapidly people clustered around various telescopes. The Sun strengthened and then dimmed as bands of cloud moved eastward repeatedly raising hopes.

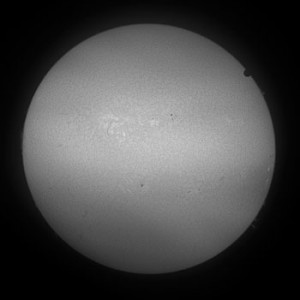

A fleeting glance of the transit just before 3rd contact. This image won the ‘Our Solar System’ category at the Astronomy Photographer of the Year awards 2012 (Pic by Chris Warren) |

Suddenly a cheer went up as a well-appointed Newtonian linked to a camera briefly displayed Venus against the disc of the Sun on a laptop screen. As suddenly as it had appeared the image was gone and everyone returned to whatever they had been discussing moments before. The Coronado telescopes were really struggling as the incredibly narrow wavelength used to create an image is blocked by the lightest cloud. I was kept busy tracking the glimmer of light in the eyepiece manually as the drives within the mount failed.

Miraculously, with only minutes remaining, breaks in the cloud allowed us to view this once in a lifetime event. With the Transit of Venus nearing completion we observed the entire disc of our neighbouring planet against the Sun’s fiery surface. At last the Coronado’s performed magnificently and I was surprised how large Venus appeared compared with easily defined Sun Spots. To see the Transit along with surface granulation and the Sun’s prominences was an added treat and it was all I could do to step away quickly and encourage others to look.

With little time remaining staff from the Royal Observatory, Flamsteed members and visitors were unceremoniously bundled past the eyepieces. I’m very pleased to say that in the short time available everyone was thrilled and relieved to have witnessed this very special alignment of heavenly bodies so close to home.

A very big thank you to everyone for making this event such a success.

Grey Lipley

A Channel 4 news report which mentions the Blackheath event can be found here.

You can also read the Guardian report on our event here.

TRANSIT OF VENUS – AN HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

by Mike Dryland

A ‘Transit of Venus’ occurs when the planet Venus passes in its orbit between the Earth and the Sun and can be seen as a tiny black disk silhouetted crossing the face of the Sun. From start to finish a Transit takes several hours. Because the orbits of Venus and Earth are tilted slightly differently, a Transit only occurs about each 120 years, in pairs separated by 8 years. At other times, when Venus ‘laps’ Earth in its journey around the Sun, a Transit isn’t seen because Venus appears to cross above or below the Sun and is lost in the daylight glare. The last Transit was seen in 2004, and there were none in the 20th Century.

The Transits in 2004 and this year, 2012, caused great excitement for amateur astronomers, but in the 18th and 19th Centuries they were very important to the ‘professional’ astronomy community. It was the second Astronomer Royal, the great Edmond Halley, who realised that measurement of a Transit could be used to calculate the size of the Earth’s orbit (theAstronomical Unit or ‘A.U.’) and hence the scale of the entire solar system. In Halley’s day the ratio of the size of the planets’ orbits to one another was known from Kepler’s Laws, but it hadn’t been possible to measure any one of them accurately. Exact knowledge of the size of Earth’s orbit would become very important because it is the vital baseline used as the only way to measure distances to nearby stars. In 1716, in his ‘Admonitions’, Halley exhorted the scientific community to make preparations to measure the Transits of 1761 and 1769 (when he knew he would be dead).

A Transit of Venus really needs a telescope to be observed, and the first reliable recorded observation wasn’t until 1639 when it was seen by English astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks from Carr House, Much Hoole near Liverpool. Horrocks was most interested in accurate prediction of the date and time and measurement of the size of Venus’ disk seen in silhouette on the Sun, which he observed by projection onto a white board. He was able to see only the last 35 minutes of the Transit but did measure the size of the disk.

To use a Transit in calculating the A.U. it’s necessary to make observations from different places a long way apart in latitude. Many expeditions to the eight corners of the Earth were organised for the Transits of 1761 and 1769. The stories of their long and arduous journeys and adventures make great reading (see book list, below) and we can only be filled with admiration for the dedication to science shown by the people who took part. One of the better known expeditions was led by Lt. James Cook to observe the 1769 Transit from Tahiti. After taking the measurements, Cook and his company sailed on to chart New Zealand and also become the first Europeans to sight and chart the coast of New South Wales.

Unfortunately the 18th Century observations were beset by problems, notably the infamous ‘black drop’ effect, an optical effect possibly caused by Venus’ atmosphere or the equipment being used. This made it very hard to determine the exact instant of the planet’s disk touching the edge of the Sun. As a result there was a wide range of different measurements leaving a big uncertainty in the exact size of the A.U.

The 19th Century Transits of 1874 and 1882 were greeted with optimism for improved results by using the new technology of photography to get better precision. Astronomers were to be disappointed. Although the results for the A.U. were improved there was still too much uncertainty.

By 2004 the Transit was no longer important to refine our knowledge of the size of the A.U. Other ways had been found to get more precise determinations, including observations of the asteroid Eros and the use of radar to measure directly the distance to Venus. But none of the thrill of the Transit has been lost. Astronomers love a spectacle and there are few better than the Transit of Venus. On June 8, 2004 the entire Transit was visible from the UK and thousands of people packed the courtyard of the Royal Observatory Greenwich to watch (using proper equipment, of course! Never look at the Sun directly or through a telescope or binoculars without a proper solar filter). On June 6, 2012 only the last hour at most would be visible after sunrise in the UK. In London, frustratingly, the Sun was hidden by cloud until the final couple of minutes, but on Blackheath near the Observatory, the crowd of spectators who had waited patiently since 5am were just as thrilled by the glimpse!

Book list

Andrea Wulf: ‘Chasing Venus; the race to measure the heavens’. William Heinemann May 2012

Nick Lomb: ‘Transit of Venus 1631 to the Present’. Experiment Apr 2012

David Sellers: ‘The Transit of Venus; the quest to find the true distance of the Sun’. MagaVelda Press 2001

Peter Aughton: ‘The Transit of Venus; the brief, brilliant life of Jeremiah Horrocks, father of British astronomy’. Weidenfeld & Nicholson 2004

Read More at —

Posted under: Blackheath, Flamsteed, Meeting Report, Transit of Venus

You must be logged in to post a comment.