March 29, 2010

Mapping the stars from antiquity to today

Prof Nick Kanas

Report by: Mike Dryland

Nick Kanas is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. He’s been running a project with astronauts and cosmonauts about human interactions in space. Nick’s hobby and passion, though, is about mapping the stars and that’s why he came to speak to us at the Flamsteed.

Nick says he’s been an amateur astronomer since he was 11 years old. He began before the days of computerised go-to scopes and he learned to ‘star hop’: finding a faint target by working from star to star guided by good old hardcopy star atlases. That’s when his interest in star maps began. He’s become a leading collector of antiquarian and all other kinds of interesting star maps and author of the book “ Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography”

Nick set the scene by talking about the different aspects of star mapping, including the spectacular (in many cases) artistry, and how celestial maps, like terrestrial, reflect the cultural and intellectual themes of their time.

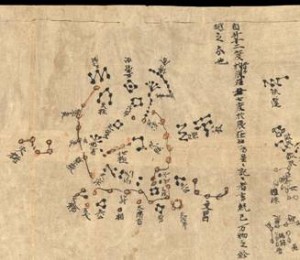

He talked us through the genesis of cataloguing and mapping the stars from antiquity, showing examples of ancient Chinese, Indian, andEgyptian systems and ‘maps’. The Chinese defined 284 constellations(star groups) needed to represent all the different aspects of their society which they believed reflected what was in the heavens. In time the Indian and Egyptian systems changed over to the Greek view exported by Alexander the Great.

Nick traced the development of Greek astronomy from the Mesopotamians via ancient Egypt, resulting in the definition of the 48 classical constellations, including the signs of the Zodiac (all animals — the same word root as ‘zoo’ — except Libra) spread around the apparent annual path of the Sun through the stars: the ecliptic. Greek belief, from Hipparchos, Eratosthenes, and others, but enshrined mostly by Ptolemy of Alexandria in his ‘Almagest’, was passed on to the Islamic astronomers and then to medieval Europe. The earliest existing work is the Farnese Atlas, a marble sculpture of Atlas bearing the globe of stars on his shoulders, and dating from the 2nd century AD but thought to be a Roman copy of a Greek original from the 2nd century BC.

The Islamic astronomers preserved and extended Ptolemy’s work adding star names (eg Algol), elements from their own Bedouin tradition, and mathematical refinement. Nick showed images from Al Sufi’s great work.

In the Europe of the middle ages the mathematical foundation of Greek thought was lost and star images in manuscript on parchment, became illustrative representations. This approach was also continued at the start of the Renaissance with the first printed images. The details of Ptolemy’s system, however, had been preserved by the Muslims, exchanged with the Byzantines, and were disseminated through Europe after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

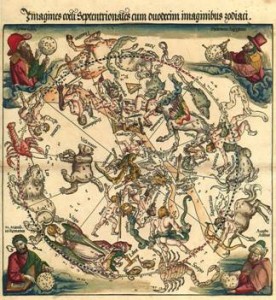

The earliest true star maps from Europe are from Durer (1515) andPiccolomini in his atlas of 1540.

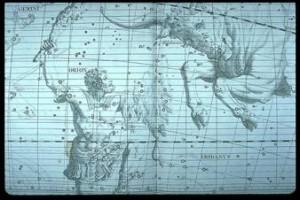

European astronomy began to flourish in the 17th Century reflected in the work of the ‘Big Four’ of star mapping: Bayer (Uranometria 1603),Hevelius (Uranographia 1687), Flamsteed (Atlas Coelestis 1729), andBode (Uranographia 1801) — strangely, all these men had the first name ‘John’ (or local equivalent!).

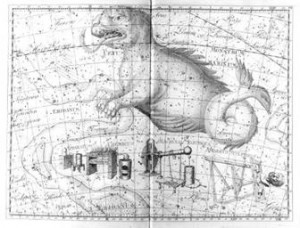

Nick showed a selection of the stunning images from this golden age. A rich profusion of constellation images is often coloured by hand later. Precision and grid systems developed quickly — Flamsteed charted 3,000 stars accurately as a basis for marine navigation; Bode charted 17,000 stars. Gaps in the knowledge of the southern stars, (invisible to the Greeks being below the horizon in Athens) were filled by the explorers then carefully charted by Halley and Lacaille. During this period constellations came and went — sometimes invented to please a patron (eg Halley’s ‘Robur Carolinum’ as a bootlick to King Charles II, and Bode’s nod to Frederick the Great).

Nick honed our knowledge and appreciation by showing examples of ‘internal’ views of the constellations (as seen from Earth) contrasted with ‘external’’ or god’s eye view (reversed laterally, as if seen from outside the stellar system looking in at the surface of a globe). He also showed the progression from ecliptic-based grids where the ecliptic is the rim of a map (important to astrology), to those as now, based on the celestial equator and useful for telescopes.

Bode’s 17,000 stars already made for an extremely complicated map with both stars and constellation images marked. As the age of the telescope progressed, more and more detail was crammed on to star maps. Soon we see the demise of constellation images on maps — they become just too cluttered. Later maps show subdued images, or just connecting lines in constellations, and then only constellation boundaries. Even the boundaries moved and varied from map to map until in 1922 the IAU agreed standard boundaries for the 88 modern constellations.

Nick ended his engrossing talk with a review of the development of the modern star atlas, itself already a dying breed with the advent of computer control and ‘planetarium’ apps. Probably the most well-known modern atlas, Norton’s, was first published in 1910 with 6500 stars and 600 ‘nebulae’. Nick showed examples from Norton’s, Beevar’s (1948 1st), Tirion (1981), and the Millennium Atlas with 1 million stars.

Originals from the golden age of the 17th and 18th Centuries may be mostly beyond the financial reach of new collectors now, but these final star atlases may be the new collector’s items of the future as the computer takes over! As in many things, we will miss the rich artistry of the past.

Read More at —

Flamsteed/Fortin Atlas Celeste 1776

Pictures from the evening [by Mike Dryland]:

Posted under: Flamsteed, Flamsteed Lecture, Meeting Report

You must be logged in to post a comment.